Lager is a beverage that is intrinsically linked to the country of Mexico. With the bright sun, warm climate, and meat-focused dishes, lagerbier feels synonymous with Mexican culture. The general public associates several Mexican-made lagers with the equator-hugging country. Corona made its name in association with relaxing on white-sand beaches. Modelo is an official sponsor of CONCACAF, the largest fùtbol association in North and Central America. And Tecate is the unofficial beer of Mexican-Americans as the city of Tecate lies in the San Diego-Tijuana region. The story of how the German tradition of lager brewing made its way into Mexico is often touted as harmless immigration. However, colonialism by Western European powers inflicted imperialism that ultimately harmed the Native communities. The stories told of German migration are often romanticized by Big Beer and average beer drinkers alike, especially when explaining what a Mexican Lager or Vienna Lager is to taproom visitors. It’s important to note who these German settlers were and how lager once solely associated with Germans came to be so closely linked to Mexico.

The lager brewing we so identify with Mexico wouldn’t take hold until the 1800s as other Western powers encouraged the movement of Europeans to the Americas. But historical context must be laid out to understand how and why Germans moved to Mexico. Spain colonized the Mexican Peninsula, beginning with the Spanish Conquest in the 16th Century. While it wouldn’t be centuries until lager brewing was established in Mexico, Hernán Cortés brought barley and the first European brewers to the Americas. The first record of beer being brewed was by Alfonsi de Herrero in 1543, just south of what is now Mexico City. Fermented beverages, of course, already existed within the Native communities. Where there is human society, there are fermented drinks. These include pulque (made from the sap of agave), tepache (made from the peel and rind of pineapples), and tesguino (made of corn and the closest Native beverage to beer). But as several European countries began to invade the Americas, the fermented drink of choice of the Western world entered alongside colonialism.

There was an initial stint of failed French colonialism from 1684-1689. But by 1690, Spain came in and took over the Mexican colonies from 1690-1821. And finally, after years of political, social, and religious imperialism, Mexico gained independence in 1821. This independence was fueled by the conservative Royalists (supporters of preserving the Spanish monarchy) who already held privilege in this society as they were primarily descendants of Spaniards. In this form of independence, the Catholic Church would still have power, Mexicans of Spanish descent would be considered equals to Spaniards, and Indigenous people would be of lesser status. Post-independence, vast waves of European migration began. The General Colonization Law was enacted and allowed for anyone, regardless of race and immigrant status, to claim land in Mexico. Note the use of claim, not purchase. This is where the German settlement begins.

German Immigration and French Imperialism

This German immigration to Mexico (and current-day Texas) occurred from 1821-1910. In the 1830s, German immigrant Friedrich Ernst set up in the Austin colony. He wrote a very persuasive letter published in a German paper that spurred a massive movement for Germans to settle in the Mexican Peninsula. It was so influential in attracting Germans to that area that he is remembered, through the white lens, as “the Father of German Immigration to Texas.” But by the 1850s, the political and social struggle between the colonizers and Native people began again. The French invaded independent Mexico in 1852 under Napoleon III’s rule, looking to establish a monarchist ally in the Americas. So while German settlement began in 1821 after Mexico won its independence from Spain, the significant influx came during France’s Second Mexican Empire.

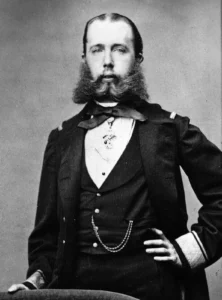

In 1864, Napoleon III appointed Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maxamillian as the Mexican Emperor. Part of his rule was focused on “developing the country” and “expanding Western culture” by opening up the nation to European immigration. Once again, we have Western European movement into Mexico directed by the colonizers of the land. The actual people of Mexico, The Mexican Republic, waged constant war with the Empire, and French troops finally began to withdraw in 1866. It was an unwinnable war due to French militant pressures and the United States refusing to recognize the Empire as legitimate. Mexico won its independence for the second time, and Maximilian was executed on June 19, 1867. While Maximilian is a product and enforcer of colonization and imperialism, he had an undeniable influence in establishing lager brewing in Mexico. During his rule, he was constantly surrounded by his close group of brewers who specialized in brewing the toasty, amber-hued, and malt-focused Vienna lager. This is the same style that is now synonymous with Modelo Negra. Maximilian’s love for lagerbier led to the development of several breweries across the country, and by 1918, 36 independent breweries were operating in Mexico.

Mexico wasn’t the only country to receive an influx of German settlers. The U.S. had the most significant wave of immigration from a single country with German immigration. The most culturally substantial beer brand born of this immigration is, of course, Anheuser-Busch. Their cultural influence in the already colonized United States appears less harmful as they were leaving an Anglo country for another (albeit it, stolen land), where most faces seemed similar to theirs. Whereas in Mexico during Maxamillian’s reign, the motivation behind lax immigration laws was to establish European cultural influence in the Americas. And even more sinister, during the Porfirio period between 1876 and 1910, President Porfirio Díaz encouraged European immigration, in part, to “whiten” the population.

The Difference Between Settlers and Immigrants

Most of these German immigrants were farmers and artisans, including wheelwrights, shoemakers, and cabinet makers. They also brought their agricultural knowledge, perfect for barley farming, which was used with great success to farm coffee beans in the Yucatan Peninsula. American Professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Jürgen Buckenau, comments that early Germans in Mexico City were “trade conquistadors… migrants of opportunity” who wanted “to get rich quickly” and “sent their profits home rather than commit significant capital investments to the host society.” As a result, they segregated themselves from Mexican society around them and did not assimilate willingly or with ease. So this begs the question of whether these German populations were indeed immigrants or settlers. Germans were invited to Mexico by Maxamillian as land settlers, one group with social power extending an offer to another group with social power in colonized land. The language is muddy across academic sources on whether these groups of Germans were indeed immigrating or settling. However, if we look at the definitions between the two, some clarity is provided:

“‘Settler’ remains a term that often applies to any individual or community that ends up permanently residing in a particular locale. Conversely, ‘immigrant’ can apply to all individuals or communities that have originated somewhere else. Thus even if ‘settler; and ‘migrant; should identify very different groups, they are often treated as interchangeable synonyms.”

So when it comes to German populations moving to Mexico, “settler” feels like a more accurate term as most of these people were not fleeing persecution but looking for an opportunity to make money to send back to Germany and not contribute to the Mexican economy or society. What the Mexican and German people did manage to find collaboration on was brewing beer. So while Mexico gained the knowledge of brewing lager, it was at the expense of erased language, religion, and culture imposed by colonizers.

Culture Exchange vs Cultural Invasion

Would lager have been brewed in Mexico if European colonization and settlement had never occurred? Perhaps not interchangeably to German methods, but it wouldn’t be impossible. Barley grows in the Americas. Native communities were already fermenting a form of corn beer (Read more in our article about Chicha de Jora here). And many Native and ancient societies constructed buildings that cool down, similar to the caves of Bohemia. Assuming that brewing beer would have never happened without European intervention implies that Native Mexicans wouldn’t have figured out how to brew on their own. It’s an imperialist mindset. Nothing good comes from colonization, and cultural exchange requires consent, or it’s an invasion.

As the populations of Native Mexicans and European settlers merged, so did the cultural associations of Mexico. We see this with architecture, especially churches, directly from Catholic missionaries. The Germans also influenced musical styles that are now so closely associated with Mexican culture. Accordions were not only brought over with the Germans but their sales were pushed amongst the people of Mexico. Some of the most iconic genres of Mexican music, including tejano, conjunto, aranchera, and banda, are descended from German polka. The dances that often accompany these genres are also rooted in traditional German step and square dances, particularly in vaquero culture. One of the essential past times for Mexicans is the sport of soccer, while brought over by the English in 1900, was also frequently played by Germans in Mexico. The settlers founded the now-defunct football club Germania FV (1915-1933), which helped cement the sport in Mexican consciousness, which similarly occurred in Brazil and Argentina also by German immigrants.

This, of course, brings us back to beer, where the German cultural influence is undeniable. Oktoberfest is usually held in several large cities with German-Mexican communities throughout the country, mainly in Mexico City, Chihuahua, and Victoria de Durango. The most notable cities that have dominated lager brewing are Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mazatlán, and Sinaloa, which were largely developed by German settlers. Mexico is one of the only Latin American countries where beer consumption is more significant than that of wine and spirits. And as the Mexican climate, culture, and cuisine have proved excellent for lager drinking, traditional German brewing has had a lasting influence on Mexican beers, with brands such as Negra Modelo and Dos Equis Ambar deriving from the Vienna Lager. Beer production remains one of Mexico’s most prominent exports, valued at over a billion USD. This is evidence of a culture taking bits of an invader’s practice and making it their own.

Legacy of Lager in Mexico

At the turn of the 20th Century, many breweries established by German settlers were now run by Mexicans, or even better, Mexicans, now equipped with the knowledge of lagering, were opening their own breweries. One of the most well-known Mexican breweries, Cerveceria Cuauhtemoc Moctezuma, was founded in 1890 during the late Porfiriato period by German brewer Wilhelm Hasse. The Germans brewed smaller batches of the traditional and high-octane bockbier for themselves, eventually gaining traction in the community. This started the taste for bock in Mexico that is still very much present today. We see the continuation of bock drinking with the traditional Mexican Christmas beer Noche Buena and Shiner Bock in present-day Texas.

In 1925, the iconic pilsner-style lager, Modelo Especial, was first brewed in Tacuba, Mexico City. The pilsner, translated to “special model,” was immediately praised for its golden brilliance and lighter body. Cervesa Modelo exploded in popularity, not only for its pale color and crushability, but because Prohibition had taken hold in the U.S. from 1920-1933 and Americans turned to their Southern neighbors for beer and spirits. To this day, Modelo is the number one imported beer in the U.S.

Today, Grupo Modelo and Cerveceria Cuauhtemoc Moctezuma control 90% of the Mexican beer market. As the creative hands slowly moved from Germans to Mexicans, lagerbier cemented its presence in the country. Lager has a stronghold on Mexico and what beer drinking in Mexico means to foreigners. We see this in the U.S. as Modelo and Tecate are served with limes. The use of lime in Mexican lager goes back to the use of clear bottles made famous by Corona. Clear bottles allow UV rays to interact with the alpha acids in hops, making the beer taste and smell “skunky.” The acidity from limes helps cover the off-flavor. But still, we receive limes with UV-protected canned beer as the association of Mexican lager and limes has been established. More recently, the term Mexican lager is loosely used in craft beer. Is it a Vienna lager of past traditions? Is it a corn-adjunct light lager? Or a marketing term? Just look at how many of your local craft breweries brew a Mexican lager with no real grasp on what it is or should be. Without a solid definition of the style, modern breweries can really do whatever they want with the term. No matter the recipe or serving technique, the association of crisp, light, refreshing lagers and Mexico is rooted in both American and Mexican culture.

French and Spanish imperialism led to introductions of brewing that has established an evolved style both in Mexico and worldwide. That does not excuse or give allowance to colonizers but explains how beer, specifically lager, has grown in Mexico. But now, American and Mexican beer drinkers are more familiar with Modelo Negra than with Vienna Lager. And while that beer defines a Mexican Lager to many, lager as a whole has come to dominate Mexico and become associated with its culture. Germans have Bavaria. Mexicans have an entire peninsula and all of the Southern American States. Over time, the German correlation has dropped from the Mexican Lager’s identity, and a commodity that descends from colonization is now a national treasure in Mexican culture. Beer isn’t the Native fermented beverage of Indigenous Mexico. But it is the modern association. And it just so happens to be a fantastic beverage for Mexico’s climate, cuisine, and people.

Sources

Settlers are not Migrants by Lorenzo Vercini

French Intervention in Mexico and the American Civil War

Small Numbers, Great Impact: Mexico and Its Immigrants 1821-1973 by Jürgen Buckenau

https://www.thtsearch.com/content/Mexican_beer/

How Mexico Learned to Polka by Renee Montagne

Mexico: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Culture and History by Don M. Coerver, Suzanne B. Pasztor, Robert Buffington